- Key Takeaways

- What Are Non-Magnetic Stainless Steel Grades?

- Why Some Stainless Steel Is Non-Magnetic

- How to Identify Non-Magnetic Stainless Steel

- Critical Applications for Non-Magnetic Steel

- Beyond the Magnet: A Deeper Look

- The Hidden Risk of Induced Magnetism

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Key Takeaways

- Non-magnetic stainless steel refers to alloys that show little to no magnetic attraction because their crystal structure and alloying elements prevent magnetic domains from aligning. Focus on the austenitic grades such as the 300 series when magnetism must be avoided.

- Popular non-magnetic grades are 304, 316, and 316L, as well as higher-alloy or nitrogen-strengthened types that improve corrosion resistance and strength. Consider these grades for medical, food processing, and chemical environments.

- Employ a powerful neodymium magnet for a quick field determination and a portable magnetic permeability meter for an accurate evaluation, which usually shows a range of 1.0 to 1.05 for non-magnetic materials. Try several locations and note results for QA.

- Ask for mill test certificates to verify chemical composition and grade prior to purchase and maintain records for traceability. Ask your supplier for solution annealing or an appropriate heat treatment to keep it austenitic and non-magnetic.

- Keep in mind that cold working, welding or deformation can induce slight magnetism in otherwise non-magnetic grades and impact sensitive equipment performance. Use tightly controlled fabrication and final component magnetic checks.

- Choose grades where you balance corrosion resistance, mechanical strength, and cost while taking into account the long-term lifecycle performance. Check with suppliers for availability and lead times. Align material characteristics with application requirements.

===

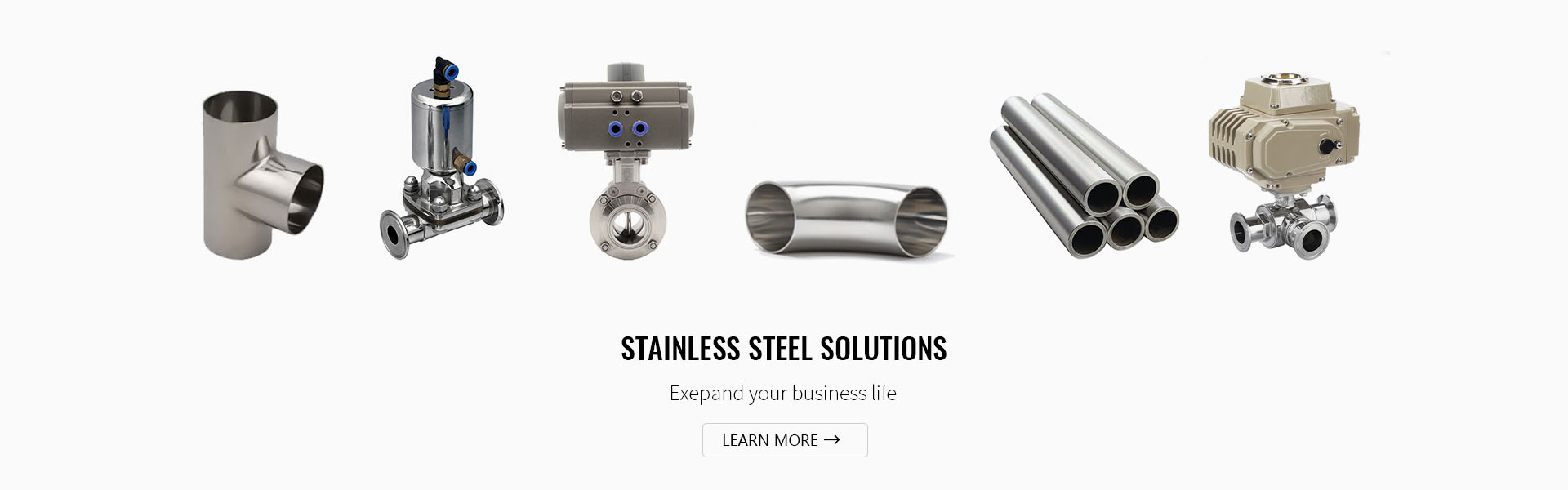

Non-magnetic stainless steel grades are stainless steel alloys that exhibit minimal to no magnetism, generally austenitic types like 304 and 316.

These grades combine both chromium and nickel to resist corrosion and maintain ductility. They are used in food equipment, medical tools, and marine fittings where magnets cannot be involved.

Selection is based on corrosion resistance, strength, and weldability. The balance of this guide details major grades, test methods, and typical applications with concise comparison comments.

What Are Non-Magnetic Stainless Steel Grades?

Non-magnetic stainless steel grades are alloys that exhibit minimal or no magnetic attraction due to their unique alloy composition and crystalline structure. They resist magnetism largely because of an austenitic face-centered cubic (fcc) lattice or other treatments that prevent magnetic domains from aligning.

They typically provide solid corrosion resistance, which is why they’re a go-to anytime magnetism would be an issue. Examples include:

- 304 (approximately 18% chromium, 8% nickel)

- 316 and 316L (molybdenum-added austenitic types)

- 904L is a high-alloy austenitic stainless steel that contains additional nickel and molybdenum.

- Nitrogen-strengthened austenitic variants

- Select duplex grades with reduced magnetic permeability

1. Austenitic 300 Series

300 series stainless steels, like 304, 316 and 316L, are the most common non-magnetic grades due to their fcc crystal structure preventing magnetic domain alignment.

304 has 18% chromium and 8% nickel plus small amounts of carbon, nitrogen and manganese. 316 adds molybdenum for corrosion resistance boost, while 316L drops carbon for weldability. Their elevated nickel and chromium content both inhibit magnetism and increase resistance to rust and chemicals, which is why cookware, surgical implements, and chemical processing equipment often use these alloys.

Remember, cold working can transform the austenite into martensite, which causes some 304 parts to become slightly magnetic. That doesn’t mean the steel is bad; it means its microstructure shifted under stress.

2. High-Alloy Austenitic

High-alloy austenitic steels incorporate elements such as molybdenum, copper, or additional nickel to endure aggressive environments while remaining non-magnetic. They maintain their austenitic structure even at high temperatures or in corrosive media.

This allows them to perform well in marine and chemical environments. Common applications include offshore systems, heat exchangers, and pharmaceutical process lines where low magnetism and corrosion resistance are required.

3. Nitrogen-Strengthened Grades

Nitrogen-strengthened austenitics employ nitrogen to increase yield strength while preserving non-magnetic behavior. They exhibit superior toughness and greater strength compared to standard 300 series, which assists in pressure vessels and structural components.

Nitrogen enhances resistance to localized attack such as pitting and crevice corrosion, making these grades well-suited to seawater and chloride-rich environments.

4. Select Duplex Grades

Certain duplex steels combine austenitic and ferritic phases, so they may be slightly magnetic but typically have less permeability than purely ferritic grades. They combine high strength with good corrosion resistance and provide moderate magnetic response.

Select duplex grades when you want strength and less magnetism, like on offshore oil platforms and some structural parts. Duplex steels aren’t fully non-magnetic but they mitigate magnetism while adding mechanical performance.

Why Some Stainless Steel Is Non-Magnetic

Some stainless steels are non-magnetic because their atomic structure and alloy composition inhibit the iron atoms from aligning into magnetic domains. All stainless steels contain iron, which is normally magnetic, but when iron sits in certain crystal lattices and is matched with stabilizing elements like nickel, the material exhibits no bulk magnetism.

Austenitic grades are the primary group that remain non-magnetic at room temperature. Processing and strain can modify that.

Crystal Structure

Austenitic stainless steels have a face-centered cubic (fcc) crystal structure that makes it difficult for magnetic domains to form and align.

In contrast, bcc and martensitic structures allow domains to align more readily, generating magnetic behavior. The stability of the austenitic phase at room temperature is key. If it remains face-centered cubic in structure, the alloy remains essentially non-magnetic.

Crystal structure | Typical phases | Magnetic tendency |

|---|---|---|

Face-centered cubic (fcc) | Austenite (e.g., 304, 316) | Low to none |

| Body-centered cubic (bcc) | Ferrite | Magnetic | | Body-centered tetragonal (bct) | Martensite | Magnetic |

Chemical Composition

High nickel and chromium content assist in stabilizing the austenitic fcc lattice. Nickel in particular is great at stabilizing austenite so the iron atoms can’t organize themselves into magnetic domains.

Chromium enhances corrosion resistance with no additional magnetism. Low carbon is good too because carbon can encourage formation of other phases which can be ferromagnetic. Keeping carbon low minimizes hazard.

Molybdenum and nitrogen are frequently used to add corrosion strength and pitting resistance but without making the steel magnetic. So 316 (Mo) or nitrogen-enhanced austenitics still are mostly non-magnetic.

Common alloying elements in non-magnetic grades are iron, chromium, nickel, manganese, molybdenum and traces of nitrogen and carbon, with nickel and manganese being pivotal in stabilizing the austenitic phase.

Manufacturing Process

Solution annealing and rapid quench assist in resetting the microstructure to a stable austenite and maintain the non-magnetic property.

Cold working, welding or incorrect heat treatment can cause austenitic grades such as 304 to become martensitic or have mixed phases, which manifests as partial magnetism. This can be a minor surface effect or a bulk transformation depending on the amount of strain.

Control in forming and proper post-weld heat treatment limits the formation of martensite and keeps the magnetic response low. Specify fabrication requirements in purchase specifications to prevent surprises in sensitive uses.

How to Identify Non-Magnetic Stainless Steel

Detecting non-magnetic stainless steel is a combination of fast field techniques and specific laboratory methods. The right identification is important for safety-critical components, medical equipment, and settings that demand corrosion resistance and non-magnetic properties.

Try these numbered ways as a roadmap to get practical, and turn them into a checklist or flowchart for repeatable sorting and traceability.

Magnet test — Bring a strong neodymium magnet in close and test for attraction at a few points. Absence of pull indicates austenitic 300-series (304, 316).

Visual and spark hints — Search for the shiny, white appearance typical of 300-series. When ground, non-magnetic austenitic steels produce short red sparks.

Nitric acid spot test — On a fresh-grinded surface, a drop of 65–70% nitric acid exhibits distinctive action to differentiate stainless varieties. Observe safety precautions.

Magnetic permeability meter — Search permeability using a portable meter. Non-magnetic stainless usually reads less than approximately 1.05. Take readings for QA.

Chemical analysis includes XRF or wet chemistry to verify chromium, nickel, and moly levels. Composition goes along with grade, too, of course.

Documents check — Examine mill test reports for grade, alloy composition and specification conformance prior to accepting material for critical application.

The Magnet Test

Take a powerful neodymium magnet and make sure to try several locations on the part surface. True austenitic grades like 304 and 316 in their annealed condition will not catch the magnet. Ferritic and martensitic steels exhibit obvious attraction, making the magnet test a quick initial filter.

Watch out for exceptions. Cold work, bending, or weld heat can induce a little magnetism to austenitic steel. A welded joint or bent flange may exhibit slight pull even when the bulk is non-magnetic.

By testing edges, flat areas, and heat affected zones, you can get a consistent picture. For in-the-field use, mark results and retest after any heat treatment. Use the magnet test just as an initial indication and back it up with a meter or certification for critical components.

Magnetic Permeability

Magnetic permeability indicates how the metal reacts to a magnetic field. Use a calibrated, portable permeability meter for an accurate reading instead of a hand magnet. Non-magnetic austenitic stainless steels usually come in at or below approximately 1.05.

Higher readings indicate ferritic or work-hardened materials. Portable meters provide numeric values that you can record for traceability and quality control. Write down the instrument model, calibration date, where you tested on the part, and the readings so someone can cross-check results later.

Material Certifications

Ask for mill or material certificates with each batch. These state the grade, complete chemical composition, including chromium, nickel, and molybdenum percentages, and what standards the material complies with.

Store copies in project files and associate them with part IDs. Approved paperwork eliminates uncertainty for safety-critical tasks and aids inspections.

Critical Applications for Non-Magnetic Steel

Non-magnetic stainless steel is critical in applications where magnetic fields need to remain unaffected and corrosion resistance and biocompatibility are significant factors. These grades, generally austenitic alloys like 316L and 904L, are selected due to their low magnetic permeability, high nickel and chromium content, and ability to withstand harsh environments and elevated temperatures.

Here are the key industries that depend on non-magnetic stainless steel and how the correct grade is important for safety and dependable operation:

- Medical devices and MRI-compatible tools

- Electronics: shields, connectors, housings

- Scientific instruments and lab equipment

- Marine hardware: fasteners, shafts, propellers, sensors

- Chemical processing and desalination plants

- Aerospace components and high-temperature parts

Medical Devices

Non-magnetic stainless steels, such as 316L and 904L stainless steel alloys, are critical for MRI-compatible surgical tools and implants, as they don’t disrupt magnetic imaging or generate electric current. These materials provide excellent corrosion resistance, which is important for implants and tools exposed to bodily fluids, while also ensuring biocompatibility. Typical parts made from these stainless steel types include scalpels, bone screws, joint stems, and components of biomedical instruments.

They provide biocompatibility and robust corrosion resistance that is important for implants and tools exposed to bodily fluids. Typical parts are scalpels, bone screws, joint stems, implantable plates and components of biomedical instruments.

Utilizing the right stainless steel families ensures that surgical instruments maintain their integrity and performance in demanding environments.

Electronics

Non-magnetic stainless steel doesn’t interfere with the electromagnetic fields that sensitive circuits depend on. It serves as shielding panels, connectors, and housings where stray magnetism may induce error or data loss.

In industrial settings with strong external fields, or where sensitive circuitry rests near metalwork, these grades maintain signal stability. It further contributes to device reliability and data integrity in long-term operation.

The choice of grade is often a balance of conductivity, finish, and corrosion resistance to suit the device environment.

Scientific Instruments

Scientific instruments require materials that won’t distort measurements. Laboratory balances, mass spectrometers, and NMR equipment often include non-magnetic components to prevent even minor magnetic distortions.

We need stable, non-magnetic environments for high precision research and repeatable results. Non-magnetic stainless steels make up structural frames as well as functional components within instruments.

Marine Hardware

Non-magnetic stainless steels are used in marine hardware to avoid compass deviation and safeguard navigation. They resist pitting and crevice corrosion in saltwater, extending service life for shipbuilding, subsea components and desalination plants.

Common components are fasteners, shafts, propellers and underwater sensors that take advantage of grades including 316L and 904L where superior corrosion resistance is needed. The appropriate grade enhances navigation safety and minimizes maintenance.

Beyond the Magnet: A Deeper Look

Non-magnetic stainless steels aren’t determined solely by a magnet test; rather, it’s crucial to consider various metals’ corrosion resistance, mechanical strength, and specific properties before selecting a stainless steel type.

Corrosion Resistance

Non-magnetic stainless steels, particularly austenitic types such as 304 and 316, provide excellent protection against rust and numerous types of corrosion. Marine, chemical, and food processing applications frequently use austenitic stainless due to chromium, nickel, and molybdenum collaborating to build a stable, passive film that impedes attack.

Molybdenum increases resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion. Use the molybdenum spot test to differentiate 316 from 304 when necessary. For parts exposed to salt spray or chlorides, look for grades with molybdenum.

Weld zones can exhibit 2 to 10 percent delta ferrite, which can make welds weakly magnetic and marginally more susceptible to local corrosion. Post-weld treatments or design modifications should be considered. If you have moisture, chemicals, or salt, rate corrosion resistance high in your selection.

Mechanical Strength

Grades like 316L offer sufficient tensile and yield strength for many load-bearing components while maintaining good ductility and toughness for forming and welding. Keep in mind that austenitics are not hardenable by heat treatment and remain relatively soft compared with martensitic grades.

Cold work raises strength by work-hardening, but cold rolling, bending, deep drawing, and welding can convert some austenite to martensite, which can cause magnetism. Solution annealing after forming can lower magnetic permeability back toward μr is approximately 1.0.

For higher strength requirements, duplex or nitrogen-strengthened austenitics provide elevated tensile and yield values while still maintaining low magnetic response in many conditions. Verify specific μr limits such as μr is less than or equal to 1.01 or μr is less than or equal to 1.05 when non-magnetic behavior is needed.

Cost and Availability

Non-magnetic grades generally cost more than ferritic or martensitic stainless because nickel, molybdenum, and nitrogen increase the alloy cost. Typical austenitics like 304 and 316 are stocked in most places and have short lead times, while specialty high-alloy, nitrogen-strengthened, or duplex grades might have longer lead times and be more expensive.

Checklist for cost and availability:

- Confirm supplier stock and current price chart.

- Check lead time for specialty heats and surface finish.

- Check necessary μr spec and any post-form annealing requirements.

- Factor in lifecycle costs: maintenance, repair, and replacement frequency.

As always, refer to supplier stock lists and price charts for current information. Total lifecycle cost often outweighs initial price. A higher-grade alloy may cost more upfront but save on corrosion repairs and downtime.

The Hidden Risk of Induced Magnetism

Non-magnetic stainless steels acquire a weak magnetic response following fabrication or service. This occurs when the metal is stressed, bent, welded, or otherwise cold worked, causing a fraction of the austenitic crystal structure to transform into martensitic stainless steel, a magnetic phase. The shift is partial and local, but it is sufficient to induce magnetism in components that were designated as non-magnetic.

Induced magnetism matters since it can influence performance in situations where magnetic neutrality is required. In medical devices, electromagnetic sensors, or MRI-adjacent parts, minor ferromagnetic tendencies can induce interference, instrument miscalibration, or undesired magnetic pull to fixtures.

In food processing, magnetism can interfere with ferrous contamination detection systems. It’s more risky for popular austenitic grades like 301, 304, and 316. Grades 304 and 316 are popular because austenite renders them non-ferromagnetic at room temperature, but their high iron composition means they can create martensite when mechanically stressed and turn partially magnetic.

Cold forming and bending are usual culprits. Whether pipes, sheets, or fasteners are formed, local deformation generates strain. That strain can induce the austenite-to-martensite transformation in vulnerable grades and in areas adjacent to welds or bends.

For instance, deep drawing 301 or heavy bending 304 can create sufficient martensite to provide a magnetic reading on a gaussmeter. Small impurities or inclusions of ferromagnetic iron in the alloy can increase the probability of post-working magnetism.

Mitigate the risk with testing and tight manufacturing controls. Test finished components with convenient handheld magnets or calibrated instruments for induced magnetism. For vital components, provide maximum acceptable magnetic readings in purchase and test on arrival.

Use processes that limit cold work where possible. Prefer hot forming, annealing, or pickling and passivation after welding to restore austenite and reduce martensite. Control weld parameters and utilize filler metals that correspond with the desired non-magnetic performance.

Monitor which grades are used. Some austenitic types and stabilized grades resist transformation more than others. Inspection, specification, and process control all work together to minimize surprises.

For sensitive cases, demand post-process inspections and corrective anneal stages when measurements indicate magnetism.

Conclusion

Non-magnetic stainless steel depends on crystal structure and alloy composition. Austenitic grades like 304 and 316 exhibit low magnetism after standard processing. Ferritic and martensitic varieties pull a magnet. Cold work can cause certain austenitic parts to become magnetic. That’s a big deal in MRI equipment, submarine equipment, food processing lines, and precision measuring instruments. Use a magnet test, lab analysis, and supplier information to select the appropriate grade. For instance, opt for 316 for salty wet applications and 304 for food tubs or kitchenware. Watch out for forming processes that can alter magnetic properties. For components, consult grade charts or inquire with vendors about austenitic grades and post-processing testing to align requirements and prevent surprise.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which stainless steel grades are non-magnetic?

Austenitic grades, such as 304, 316, 310, and 321, are generally non-magnetic stainless steel types. In contrast, ferritic and martensitic steels exhibit magnetic properties, making them suitable for applications involving magnetic separation.

Is 304 stainless steel non-magnetic?

New, annealed 304 stainless steel is essentially non-magnetic, but cold working or welding can induce slight magnetic properties. Expect an extremely low magnetic response unless heavily worked.

Is 316 stainless steel non-magnetic?

Yes. Annealed 316L stainless steel is non-magnetic due to its austenitic material structure, but welding or deformation may introduce some magnetic properties.

How can I quickly test if stainless steel is non-magnetic?

Take a small magnet to test the magnetic properties of the metal. If it doesn’t stick, the steel is likely a non-magnetic type, while weak attraction may indicate partial conversion to a magnetic phase.

Can non-magnetic stainless steel become magnetic over time?

Yes. Cold work, welding heat, or mechanical stress can convert the austenitic structure to martensitic stainless steel, inducing magnetic properties. Corrosion or service conditions do not just make metals magnetic, either.

What applications need non-magnetic stainless steel?

Employ non-magnetic grades in MRI suites, precision instruments, electronics, naval environments and explosive ordnance disposal. They stop interference with sensitive equipment and minimize magnetic hazards.