- Key Takeaways

- The Core Components of Stainless Steel

- How Stainless Steel Alloy Composition is Determined

- What Types of Stainless Steel Alloys Exist?

- The Role of Minor Alloying Elements

- Beyond the Formula: The Unseen Influences

- The Future of Stainless Steel Alloy Design

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What are the primary elements in stainless steel alloys?

- How does chromium percentage affect corrosion resistance?

- Why is nickel added to stainless steel?

- What are common stainless steel types and their uses?

- How do minor alloying elements influence properties?

- Can heat treatment change stainless steel properties?

- What trends are shaping future stainless steel alloy design?

Key Takeaways

- Stainless steel alloys are structured around iron with chromium, nickel, carbon, and/or molybdenum defining corrosion resistance, strength, and hardness. Make sure to have at least 10.5% chromium for fundamental rust resistance and pick grades by element ratios.

- Chromium forms a passive oxide layer that prevents rust. Nickel enhances ductility and toughness for austenitic grades. Carbon regulates hardness but can reduce corrosion resistance when excessive. Molybdenum increases resistance to pitting in aggressive environments.

- Choose alloy composition according to application, environment, and life-cycle cost. Compare needed corrosion resistance, mechanical properties, and total cost, not material cost alone.

- Members of the main stainless steel families — austenitic, ferritic, martensitic, and duplex — address different applications like food processing, automotive trim, cutlery, and chemical and marine service.

- Trace elements such as nitrogen, manganese, silicon, and copper adjust strength, corrosion characteristics, weldability, and formability. Define controlled additions to satisfy performance criteria.

- Control trace elements, impurities, and microstructure throughout manufacture and employ standardized specifications and testing to achieve uniform corrosion resistance and mechanical properties.

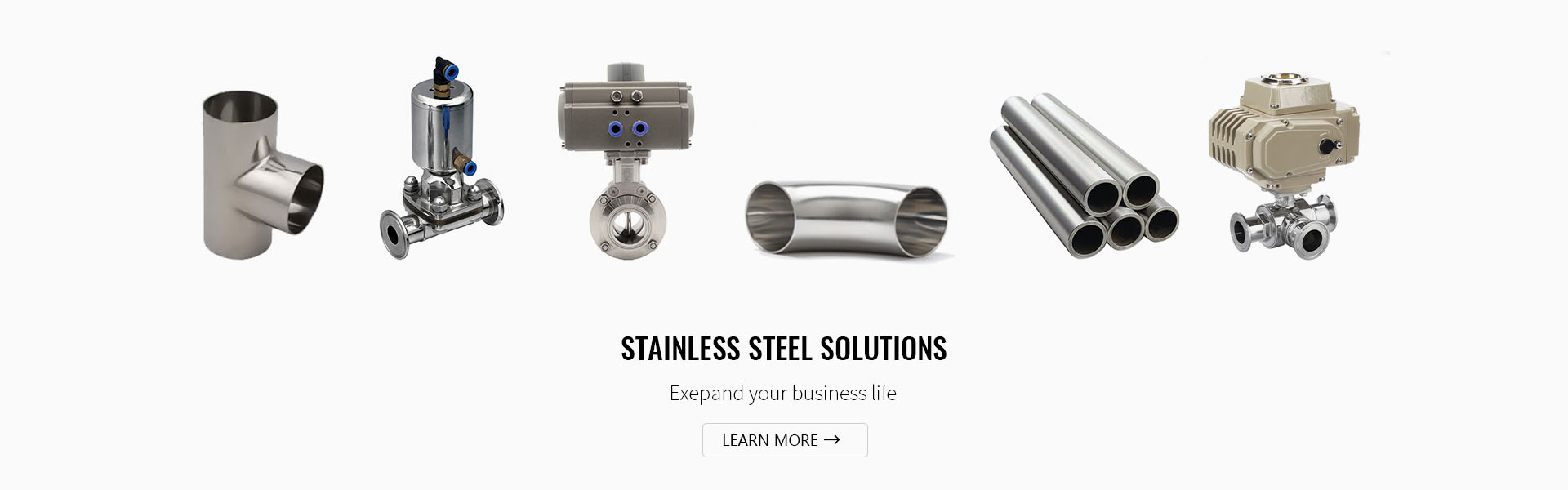

Well, stainless steel alloy is primarily made from iron, chromium, and nickel.

Chromium provides corrosion resistance through a passive oxide film, and nickel imparts strength and ductility at room and elevated temperatures.

Other typical additives include manganese, molybdenum, and carbon, each adjusting hardness, weldability, and pitting resistance.

Grades differ by percentage of these elements, which defines application in cookware, medical instruments, architecture, and industrial machinery.

More information below the fold.

The Core Components of Stainless Steel

Stainless steel is an iron-based alloy characterized by a minimum chromium content of approximately 10.5%. The blend of components, iron, chromium, nickel, carbon, and molybdenum, determines the alloy’s corrosion resistance, strength, and formability.

Adjusting their ratios produces different stainless families and grades that are best for specific environments and applications.

1. Iron

Iron is the foundation metal of all stainless steels. It provides the majority of the metal matrix and the majority of mechanical strength observed in structural and sheet products.

Since pure iron rusts immediately, alloying is necessary to achieve corrosion resistance and functional performance in use. The iron is balanced with chromium, nickel, and minor additions such as manganese or nitrogen to form the final microstructure and characteristics.

Iron’s role is both structural and economic. It keeps costs reasonable while letting alloying elements be tailored to meet specific needs, from kitchenware to pressure vessels.

2. Chromium

Chromium is the mark of stainless steel and that has to be at least 10.5% to dub the alloy “stainless.” Chromium develops a thin, passive chromium-oxide film on the surface that prevents oxygen and moisture from forming reactive iron oxides.

Higher chromium levels, up to about 18% in many common grades, increase resistance to general oxidation and to harsh atmospheres. Chromium content is the primary distinction between stainless and regular carbon steel and helps identify which environments a grade will withstand.

Chromium is teamed with molybdenum and nickel, which together enhance performance in acidic or chloride-rich environments.

3. Nickel

Nickel, which stabilizes the austenitic phase, is at the heart of 300-series stainless steels. Added nickel, occasionally up to 8 to 20 percent in some alloys, improves ductility, toughness, and ease of forming.

Nickel enhances corrosion resistance, particularly in acidic or chloride environments, and influences magnetic response. Higher nickel usually results in a nonmagnetic, austenitic structure.

Manganese and nitrogen occasionally replace some of the nickel in order to reduce cost while maintaining austenite. Grade examples include 304, which contains about 18% chromium and 8% nickel, and 316, which has added molybdenum.

4. Carbon

Carbon is a powerful hardener in steels, kept low in stainless grades. It is generally well under 2%, often under 0.08% in “L” low-carbon versions.

Higher carbon increases hardness and strength but can result in carbide precipitation at grain boundaries, which leads to intergranular corrosion. Carbon control is essential in weld and thermal cycling applications.

Other grades are fabricated with slightly more carbon for precipitation-hardening, where you exchange ductility for increased yield strength.

5. Molybdenum

Molybdenum is added in small quantities to combat pitting and crevice corrosion, especially in marine and chemical environments. Grades such as 316 contain molybdenum to enhance chloride resistance.

Mo helps retain strength at elevated temperatures and refines corrosion performance when added in combination with chromium and nickel. In aggressive environments or specialized alloys, elevated Mo levels are employed for additional protection.

How Stainless Steel Alloy Composition is Determined

Stainless steel composition is determined according to mechanical requirements and corrosion resistance for a specific application. Designers and engineers select alloying elements like chromium, nickel, molybdenum, carbon, nitrogen, and trace elements to adjust properties.

An 11% chromium content and above is what makes stainless steel. Nickel at or above 8% stabilizes the austenitic structure in many common grades. Molybdenum, normally between 0.5% and 3%, is included where pitting resistance is important.

Carbon, ranging from 0.01% to 1.2%, raises hardness and tensile strength, while nitrogen can boost both strength and pitting resistance. Manufacturing processes such as AOD, or argon oxygen decarburization, trim carbon and sulfur to target levels.

Sulfur is maintained low, approximately 0.01% to 0.03%, to facilitate machinability without compromising corrosion performance. The final blend depends on the environment the part will encounter, expected lifespan, and manufacturing.

Application Needs

End-use completely dictates alloy and grade selection. Medical implants require great corrosion resistance and biocompatibility, thus low-carbon, nickel-containing austenitic grades are widespread.

Kitchenware rates cleanability and corrosion resistance in food media. Construction pieces could prefer higher strength or duplex grades where chloride exposure is a danger.

- Medical devices (surgical tools, implants)

- Kitchenware and food processing equipment

- Construction and architectural panels

- Chemical plant piping and heat exchangers

- Marine fittings and offshore structures

Varying industries prioritize corrosion resistance, strength, and formability in varying order. For instance, chemical processing values pitting resistance and frequently requires molybdenum-bearing alloys, while cookware values formability and cost.

Cost-Effectiveness

Selecting an alloy optimizes the necessary performance with material and process cost. Higher nickel and molybdenum contents increase raw material cost, occasionally significantly, yet can extend service life in aggressive environments and minimize replacement and downtime costs.

Compare initial cost against lifecycle cost: a pricier alloy with molybdenum may be cheaper over 20 years than a low-cost grade that corrodes sooner. For benign environments, inexpensive ferritic or low-nickel austenitic grades provide sufficient performance.

Procurement factors in global availability and price volatility of elements such as nickel.

Manufacturing Processes

Alloy composition impacts weldability, machinability, and forming. High-carbon and some alloy contents make for difficult welding and need preheat or post-weld heat treatment.

Certain grades are designed for drawing and forming, while others, such as duplex steels, are more robust but less ductile and require specialized forming techniques. Hardness and impact tests define usage standards, while production limits, such as maximum sulfur or silicon levels, reflect furnace control and downstream needs.

Match alloy choice to fabrication capability. If a plant only does simple welding and stamping, choose grades that suit those processes rather than exotic blends that need specialized handling.

What Types of Stainless Steel Alloys Exist?

Stainless steel is divided into families, each with a typical chemistry, microstructure, and properties, including austenitic types known for their excellent corrosion resistance. The choice between these families is based on the corrosion resistance needed, strength, formability, and application of stainless steel components.

- austenitic

- ferritic

- martensitic

- duplex

Austenitic

Austenitic stainless steels represent the largest family, accounting for roughly two-thirds of the world’s stainless steel production. These steels are high in chromium and nickel, which contribute to their inherent corrosion resistance and face-centered cubic crystal structure that provides excellent toughness, even at low temperatures. They are often used in various applications, including stainless steel cookware and industrial equipment.

This family splits into two subfamilies: chromium-nickel alloys and chromium-manganese-nickel alloys. The 200 series comprises chromium-manganese-nickel alloys that utilize more manganese and nitrogen to compensate for reduced nickel levels while maintaining the austenitic structure. These stainless steel compositions are particularly valued for their outstanding corrosion resistance and are non-magnetic in the annealed condition.

Extremely formable and weldable, austenitic steels are widely used for many stainless steel sheets and tube applications. Popular examples include Type 304, which contains approximately 18% chromium, and Type 316, both commonly employed in food processing, chemical plants, and corrosion tests involving acidic hypersaline brine and geothermal research.

Ferritic

Ferritic stainless steels are mostly chromium-based with low nickel content and a body-centered cubic ferrite crystal structure. They’re magnetic and typically less expensive than austenitics because they contain little to no nickel.

Ferritic grades provide good corrosion resistance in numerous situations. Certain Fe-Cr-Al alloys contain as much as 5% aluminium to increase electrical resistance and oxidation resistance at high temperatures.

Ferritics are moderately strong but less ductile and more difficult to cold-form than austenitics. Typical applications include automotive trim, appliances, and architectural panels where moderate corrosion resistance with a magnetic response is required.

Martensitic

Martensitic stainless steels have more carbon than ferritic or austenitic grades and can be hardened by heat treatment. They are magnetic and can achieve high hardness and strength with quench and temper cycles.

These alloys typically exhibit only moderate corrosion resistance relative to their austenitic and duplex families. Martensitics go back to early patents like Elwood Haynes’ 1912 filing.

Common uses are knives, surgical equipment, valves, and tools where hardness and edge retention are important.

Duplex

Duplex stainless steels blend austenitic and ferritic microstructures to strike a balance in properties. They provide strength over austenitics and better corrosion resistance than many ferritics.

Duplex grades resist stress corrosion cracking and chloride-driven pitting particularly well. They are suitable for chemical processing, oil and gas, and marine environments.

They fill the space where strength and corrosion resistance are both important.

The Role of Minor Alloying Elements

Minor alloying elements are added in small quantities to stainless steel to tweak properties that the major elements (iron, chromium, nickel) established. These elements influence strength, corrosion behavior, weldability, formability, and high temperature performance. Their content is carefully controlled because strategic changes can produce significant effects, good or bad.

Here’s a bullet list that describes some of the key minor elements and how they’re used.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen strengthens and enhances pitting corrosion resistance, particularly in chloride-laden environments. It is an austenite-former, increasing austenite stability similarly to nickel, so it aids the retention of ductile and tough steels. Nitrogen enables designers to reduce nickel content but maintain similar mechanical and corrosion properties, a benefit in situations where nickel prices or availability is constrained.

It is important in high-performance austenitic and duplex grades used in chemical plants and seawater systems.

Manganese

Manganese frequently substitutes for some of the nickel found in specific stainless grades and aids in stabilizing the structure. It enhances hot workability and hot ductility, which facilitates rolling and forming at high temperature and diminishes surface cracking during processing.

Manganese serves as a deoxidizer at melting and increases strength and hardness in the finished alloy. Beware: too much manganese can harm corrosion resistance and change phase balance, so amounts are kept in check.

Silicon

Silicon is primarily a deoxidizer during melting. It increases oxidation resistance at elevated temperatures, which is a plus for components exposed to heat, and it enhances casting fluidity and increases electrical resistance in certain applications.

Too much silicon tips steel toward brittleness and reduces ductility, so its application is a trade-off between process requirements and ultimate mechanical characteristics.

Copper

Copper contributes acid resistance and minimizes work hardening during forming to enhance formability. It improves corrosion resistance in certain environments and is purposefully incorporated into a few austenitic and ferritic grades for niche applications.

Copper may enhance machinability and resistance to marine and atmospheric durability. Its content is kept low to prevent undesirable phase formation or decreased high-temperature stability.

Other notes: Phosphorus and sulfur commonly appear as impurities. Small amounts of sulfur can help machinability while decreasing corrosion resistance. Phosphorus may assist in reducing machining time but can embrittle if excessive.

Titanium ties up carbon as stable carbides when added at roughly 0.25 to 0.60 percent, stopping chromium carbide formation and maintaining grain-boundary corrosion resistance. Tungsten is found in specialty grades to increase pitting resistance.

These minor elements are tightly controlled to ensure they do not adversely affect performance.

Beyond the Formula: The Unseen Influences

The baseline chemical formula of a stainless steel grade provides a first-order glimpse of performance, but trace elements, impurities, and microstructure alter how that alloy behaves in service. A small change in composition or heat treatment frequently shifts corrosion resistance, strength, or toughness more than a nominal change in chromium or nickel might suggest. By monitoring and controlling during melting, forming, and finishing, they keep properties within design limits.

Beyond these formulas, advanced testing, including chemical and mechanical tests as well as microstructural exams, ensures consistency and catches deviations before parts see service.

Trace Elements

- Checklist of trace elements and effects:

- Nitrogen boosts strength and pitting resistance. It is useful in duplex and austenitic grades.

- Manganese improves hardenability and tensile strength. It substitutes some nickel in cost-sensitive mixes.

- Silicon aids deoxidation but can reduce ductility at high levels.

- Carbon raises hardness but can lower corrosion resistance if not controlled.

- Copper, titanium, and niobium are used for specific benefits like stabilization or enhanced corrosion resistance.

- Lead or excessive sulfur improve machinability but can harm corrosion resistance.

Trace elements may improve or reduce mechanical and corrosion properties depending on quantity and interaction with main alloying elements. Even ppm-level changes of some elements impact passivity, weldability, or localized attack.

Standards impose stringent limits on trace elements in order to guarantee consistent performance from supplier to supplier and from mill to mill. Intentional additions can be added for machinability, grain refinement or to meet target mechanical properties, and these additions are all specified and tested to ensure they don’t introduce undesirable side effects.

Impurity Control

Reducing impurities like sulfur and phosphorus is essential to performance. Sulfur and phosphorus segregation at grain boundaries can cause brittleness, lower ductility, and greater susceptibility to intergranular corrosion. Oxygen and hydrogen can create porosity or hydrogen embrittlement in sensitive grades.

Modern steelmaking methods, including vacuum degassing, ladle refining, and controlled solidification, emphasize impurity removal to achieve high-quality alloy specifications. Inline sensors and lab assays monitor impurity levels throughout manufacturing.

Quality control connects chemistry to performance with non-destructive testing, tensile tests, and corrosion screens. Sturdy ingredients come from a process that connects raw material inspection, process monitoring, and end verification.

Microstructure Impact

The microstructure of atoms and phases determines hardness, toughness, and corrosion behavior. Grain size, phase balance of austenite, ferrite, and martensite, and precipitates modify mechanical and electrochemical behavior.

Heat treatment and cooling rates alter grain size and phase fractions. Slow cooling can permit carbides or sigma phase to form, decreasing corrosion resistance and toughness. Quenching can trap phases that strengthen but reduce ductility.

Microstructure influences hardness, toughness, and corrosion resistance in expected ways. Metallographic analysis and hardness mapping ensure that final parts align to design intent. Manufacturing steps, such as forging, casting, and welding, can introduce defects or change microstructure. Environmental or adjacent materials exposure impacts long term performance.

The Future of Stainless Steel Alloy Design

The industry is transitioning to increasingly purpose-built stainless steel components that satisfy more stringent performance and environmental objectives. New grades will emerge to address challenging applications in the energy, medical, and aerospace fields. These grades will strive for not only higher strength and better corrosion resistance but predictable long-term service and lower life-cycle impact.

Expect new stainless steel grades to continue to be developed for demanding applications. Expect families tuned for specific stressors: fatigue in wind-turbine hubs, creep at high temperature in power plants, and bio-compatibility in implants. The 200 series and other newcomers demonstrate that minute alterations in manganese, nitrogen, and nickel equivalents can generate improved formability and corrosion performance at a reduced cost.

Additive manufacturing frees design space. Using 3D printing, makers are able to create lattice cores, functionally graded parts, and thin-walled shapes that were previously unreachable, boosting strength-to-weight ratios while conserving material.

Sustainability and recycling will influence future stainless steel compositions. Recyclability will be a fundamental spec, not an afterthought. Designers will select alloy mixes that can tolerate more scrap content without sacrificing properties. Life-cycle modeling will drive choices: lower embodied carbon alloys, fewer critical elements, and formulations that ease downstream separation and reuse.

This transition impacts supply chains worldwide and supports compliance with regulations and buyer demands for low-carbon materials. Outline stainless steel’s future, emphasizing the movement toward more corrosion-resistant, environmentally sustainable alloys. Nanostructured steels and surface-engineered grades hold out the prospect of enhanced passivation and extended lifespan in chloride-rich or acidic environments.

Computational modeling accelerates this advancement by allowing teams to virtually screen thousands of stainless steel compositions, predicting phase stability, corrosion propensities, and mechanical response prior to manufacturing lab batches. This shortens time to market and minimizes waste.

Promote keeping an eye on new technologies and advancements in stainless steel production. Keep watch on integrated approaches that combine stainless steels with composites or ceramics to make hybrids that use metal where toughness is needed and composites where weight matters.

Follow breakthroughs in powder metallurgy, cryo-processing, and nano-scale refinement that enhance creep resistance and fatigue life. Note persistent challenges that include balancing cost, manufacturability, and mixed properties, avoiding reliance on scarce elements, and ensuring that new alloys can be scaled for production without unexpected failure modes.

Driven by additive methods, better models, and sustainability rules that reshape composition choices.

Conclusion

Stainless steel combines iron with chromium, nickel, and carbon. Chromium provides rust resistance. Nickel provides shape and rigidity. Carbon hardens the metal in small doses. Manganese, molybdenum, and silicon tune workability and corrosion resistance. Trace elements like titanium, niobium, or copper stabilize grain size and weld strength. Heat and work transform grain and phase. This mix alters strength, ductility, and corrosion behavior.

Alloy stainless steel components. Type 304 fits food equipment and kitchens. Type 316 works close to salt and sea. Ferritic grades fit automotive parts on tighter budgets. Designers select alloys by load, temperature, and exposure. Sample or lab test for final selection. Know the grade, match the use, and test before you buy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary elements in stainless steel alloys?

Most stainless steel components consist of iron, chromium (greater than or equal to 10.5 percent), and carbon, with chromium providing excellent corrosion resistance. Many grades also include nickel for toughness and formability.

How does chromium percentage affect corrosion resistance?

More chromium enhances the protective oxide layer and inherent corrosion resistance. A minimum of 10.5% and 16-18% in stainless steel compositions provides much better resistance for a lot of environments.

Why is nickel added to stainless steel?

Nickel stabilizes the austenitic structure in stainless steel components, enhancing toughness, ductility, and resistance to corrosion and high temperatures.

What are common stainless steel types and their uses?

Austenitic stainless steel components (300 series) are often utilized for food and medical applications, while ferritic stainless steel is commonly employed in automotive and appliance manufacturing, showcasing the versatility of these resistant steels.

How do minor alloying elements influence properties?

Elements such as molybdenum, titanium, niobium, and nitrogen enhance the performance of stainless steel components by providing increased strength, resistance to pitting, and stability.

Can heat treatment change stainless steel properties?

Yes. Heat treatment and cooling control microstructure, strength, hardness, and excellent corrosion resistance of stainless steel components. Certain grades are heat-treatable, while others accrue properties via cold work.

What trends are shaping future stainless steel alloy design?

Designed to reduce critical metals in stainless steel components, improve sustainability, and customize stainless steel compositions for extreme environments. Advanced modeling and 3D printing accelerate creation.